Learnings from building the largest digital marketing agency in San Diego, acquiring companies, doing a Private Equity backed rollup gone sideways and from five subsequent exits since.

01

Critical Terms and Deal Points that matter and why you need advisors to protect you.

02

How aggressively pursuing growth can lead you to make decisions that put you in a risky situation.

03

The inevitable transforming journey of an exit towards personal growth.

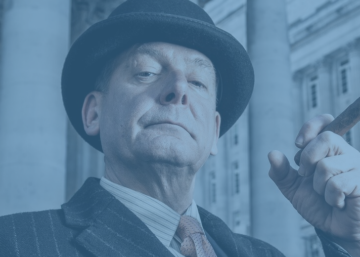

Andreas Roell is Managing Partner at Analytics Ventures, a Venture Studio Fund focused on starting new ventures with artificial intelligence and machine learning at their core. In this capacity, Andreas is spearheading the fund’s incubation and operations responsibilities that leads ventures from inception, to product validation and operational acceleration. Under his direct leadership are currently ventures ranging from health, advertising, business intelligence, and cloud solutions.

Prior to joining Analytics Ventures, Andreas was the co-founder and Chief Executive Officer of EGM Worldwide, headquartered in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. In this capacity, Andreas partnered with leading Arabic entertainment companies to develop the regions’ largest video-on-demand platform. The company was acquired in 2013 by Rotana Media Group.

Prior to founding EGM Worldwide in 2012, Andreas was the Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Geary Group, a global digital agency. Over the course of his 12-year tenure, he took the agency from inception and a $20,000 investment to making it the fourth largest independent search agency globally with offices in the North America, Asia, Europe and over 250 employees worldwide. The agency was acquired in 2012.

Suggested Resources

Full Transcript

Brandon: Welcome to “Exits and Acquisitions” podcast. Today, we’ve got my good friend Andreas Roell on the show. He has his MBA from USD. He’s currently running a VC company focused on artificial intelligence called Analytics Ventures. They’ve invested and incubated six companies so far. He’s here to tell us about how in 2000 he started a company called Geary Group. They went from about 2000 to 2012. They bought five companies and then ended up exiting to a private equity firm. He’s started a total of eight companies so far and has three exits. And he looks really good in a pair of lederhosen. So thanks for coming on, Andreas.

Andreas: Thanks, Brandon. Thank you.

Drew: He also was a professional soccer player, Brandon.

Brandon: Oh, he was a professional soccer player. I forgot about that.

Andreas: When I was faster than I am right now. Thanks, Brandon. Glad to be here.

Drew: So, Andreas, I also know you and remember when you…I believe it was the largest marketing, you know, digital agency in San Diego at a point. Is that correct?

Andreas: Yeah, at one point we were able to hit the summit of the mountain. You’re right.

Drew: Well, congrats on that. And so Geary, I believe Interactive or Geary Group. Tell me a little bit about kind of the early days of building your digital agency.

Andreas: Yeah. I mean, it’s your typical call it American story, if you will. I mean, for me it was, as you probably will tell, as a listener, that at one point, you’ll realize that I’m not born and raised here. I’m from Germany originally. So, you know, I grew up in this whole other part of the world, dreaming about the American dream. And I was fortunate enough to actually live with that particular venture. During the time I had graduated from USD for my MBA, and I was trying to figure out what can I do in order to stay in the country. And at the end of the day, I found a way of partnering up with an advertising agency out of Las Vegas, hence the name Geary, that still exists.

And I decided I’m just going to convince them that…back in the days in 2000, not many people knew what digital was, what interactive was. And I convinced them simply to say, “Hey, if you offer interactive services, you’ll make yourself be very, very cool and hip and we’ll help you win your clients.” They went for it. They allowed me to use the name Geary, and at the end of the day it was me and a co-founder, which was my nephew who knew the technical side and the being the guy who can talk and we found ourselves working out of his house. He was a surfer. I had to literally chase him from the beach, from the waves onto the computer so we actually get work done.

But we were the typical story behind the wooden desk, I like to call it, with one computer and just figuring out what we need to do in order to get clients and grow from there. We started out and we got lucky with that relationship that I had mentioned that they brought us into a pitch with the Sahara Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas, which doesn’t exist nowadays anymore. And we ended up being the only guys offering advertising services and interactive services. And it turned out that was exactly the focus that they had because casinos were starting to feel the pressure from Expedia and Priceline and others.

So from there it went. I remember the day when the CMO looked me in the eyes of contract signing and asked me, “Do you actually know what you’re doing?” And I said, “Absolutely, I know.” And here, Brandon, we signed over a quarter million dollars’ worth of a contract to build a website. And I went home and I said to my partner, “We now freaking have to figure out what to do with it.” And they went. So it’s a typical, I call it, American dream story where you have all the confidence in the world, you believe in yourself, you call it pre-sale what you have in place, and you make it happen.

So we were lucky enough to work with pretty much all the independent casinos over the years and grow the organization organically. All cash flow. I didn’t take any outside money until 2005, 2006 when we were in a place where I just had made the decision of, okay, organic growth gets you at a certain place. But being a former athlete, as you had mentioned, I guess you can say I’m always fairly ambitious and just doing okay is not good enough for me. So I always wanted to test my limits and decided to get private equity for the purpose of doing a roll-up.

So that’s a strategy that I have defined as part of the growth story where I found that the world in the U.S. at that point existed of many small to medium-sized interactive agencies, web development firms and I felt that they were right for consolidation. And, you know, we’ve done a pretty good job in terms of operational processes, set up systems, message brand, all of those and I felt it was the right move for us to say, “Okay, give us a good amount of money that we can use in order to roll-up companies, which is what we did in 2005. Funny story around that is it was Bear Stearns but then we all know the story about Bear Stearns. So I got kind of like got in that motion as well.

Drew: Well, you hit a couple points. One is I think a mark of an entrepreneur can be that you sell something before you have it. I remember selling a web-based product and we had to like code it overnight. We were like, “Oh, crap we actually had to deliver on this.” So you’ve got that notch on your belt. So how did you go about…go ahead.

Andreas: No, not, that’s exactly right. I mean, the only cautionary point was, you know, maybe back then it was foolishness that helped me but I do caution sometimes to always do that. But that’s the only point I wanted to say.

Drew: Yeah, I always think that entrepreneurs to be kind of visionary they have like something is wrong with their brain and right with their brain where they don’t kind of understand time and space so they make decisions based on kind of a vision for what can be and then they’re like, “Oh, crap, this actually has to be built.” So that’s one thing I’ve seen a couple times. But you went out after private equity. Like what was that process like? How did you get a private equity firm to finally say, “Yes, we want to put some money behind you?”

Andreas: Yeah. I’m sure many of your listeners, they own businesses and they have growing businesses are familiar with call it once a month of a call of an associate of a private equity firm just knocking on your door and of course sending you a letter back then and saying, “Hey, we’ve been watching your business and we would like to put money to work.” So that was one of those situations where I guess the frequency of these messages or outrageous start getting larger, which made my mind work and I started having conversations with various different firms. I mean, reality from that is that you have to be very careful not to waste too much of your time because, first of all, all these associates are being hired for fishing exercises without really…I mean, they pretend to know something about your business, but they really don’t.

So one, I guess, message for your audience is just a very quick in terms of your qualification, in terms of what type of companies they invest in, and which category, how much money they put to work, what valuation process is. And I didn’t know this at first, but I got myself in these conversations. And after a period of time, you know, I found myself being an active chat with a with a group for private equity firms or venture capital firms, whatever they were. And I kind of like kept talking and I started devising or creating a vision or strategy because they start pushing me about, “What would you do with the money if we give it to you?”

So, again, on the fly to an extent, I started thinking about what am I actually going to do with that and how do I create a filter or qualification process around that whole roll-up strategy that was great in general of a message but there was not much substance to it? And when I was going through that more detailed orientation, one of them, again, was Bear Stearns, started really aligning itself with us because the partners of that equity group or the fund was very heavy around media and advertising background and we started getting into a conversation where I felt, “Okay, they speak my language and they understand my needs and what I’m trying to do.”

So I narrowed down to one. Got myself in negotiations, if you will. But at the end of the day, now looking back and having much more experience, I didn’t negotiate much. I pretty much just looked at how they’re going to give me money, they’re allowing to let me do what I want to do. Documents, “Here, attorney, please look at it but don’t do a lot of redlining because I want to get the deal done.” And so I would say I ended up doing a fairly accelerated deal within a three-month period after I identified the lead and then there was off to the races.

Drew: You know, what I remember is if an entrepreneur or someone listening wants to have those phone calls getting into kind of the local city kind of fastest-growing company list and then Inc. 500 to 5,000, it was just like an exponential number of private equity phone calls. Any experience share on that?

Andreas: Yeah, I mean, exactly right. When I was talking about the acceleration of those type of calls and outreach because, I mean, at the end of the day when you look at the business model now sitting as a venture capital too, got more insights on the other side of the table, I mean, that’s at the end of the day for them the target list. If they start seeing these Inc. 500 or 5,000 or fastest-growing list, in particular, cities and then they just categorize by the industry that these companies found and then they say, “Okay, this is a new one I haven’t heard of, I’m going to start popping myself into it.” I mean, that’s what I felt as well. And like I said, the key areas for an entrepreneur in retrospect is how can I digest that as quickly as I can from a qualification side so I don’t waste my time with somebody that just puts a lot of money in front of my face, but at the end of the day, it’s not a good match?

Drew: Knowing Brandon, he gets excited about deal terms. So I’m going to pause for a moment and let Brandonmaybe ask you some questions about that.

Brandon: Yeah, absolutely. So it was a three-month process. That sounds pretty short. Is that three months from when they first called you to when you had a deal signed, money in your bank account? Or was that kind of the started due diligence or how did that process work?

Andreas: Yeah. So I would say this frontend…I never really looked at the timeline. But I would say it was probably a half-year process from the ones I emotionally and strategically committed myself to. I wanted to get money and I wanted to do a roll-up to then actively talking over a period, call it a quarter, with multiple firms and then narrowing it down to one where I was shipped out to New York to have multi-day meetings in order to, again, present the plan and start talking through some of the terms and the approaches of what to do with the money. The largest component, as always, is the legal component.

So I would probably categorize it as a month-and-a-half of back and forth. But that’s even fairly short because the private equity firm at that level of where we were, and we got $6 million, they didn’t do too much due diligence or at least this firm didn’t do too much due diligence because they just more or less, you know, being $100 million fund or so, for them it was a diversified approach, early stage, know our risk environment. And so due diligence and interaction with them from a strategic level was fairly reduced at that point.

Brandon: Yeah, got it. So $6 million. What were the other terms of the deal? How much did they take and also like how big was your company at that point?

Andreas: The company, I think, at that point was that a clocking [SP] rate of about $12 million is what I probably recall. I don’t have the exact numbers in my head. In retrospect, right, I mean, I was in the service business. So service businesses, as Drew knows very well, get a quite handicapped multiplier and valuation model. Drew, obviously you were sitting I believe on the better side of the table than I was but we were timing material-based, fixed price project bids with clients that have not a continuous annuity type of revenue model. So we got checked on the on the multipliers side obviously dealing with the private equity group, me being inexperienced, I ended up being at a…they do it based on profitability and I got it applied on the multiplier on the profitability at that point. That was pre-money.

And what was the other question again, Brandon? The other terms, I’m sorry. The other terms were what came out of all of this was which in some of the big learnings where I did not put a lot of emphasis on was the whole process around governance and decision-making processes that comes out of the ask or the preferences that the private equity firm had. So for me, as I had mentioned in the introduction about the story, my whole focus was, “Oh, I want money and I want to execute my plan.” Everything else in terms of what’s the board competition, what’s the decision-making process, what’s the preferences at an exit [inaudible 00:26:30] were, on the one side ,Japanese to me because I didn’t have the experience and I didn’t do a good job in bringing advisors to the table and that.

And secondarily, you know, I was just in such a rush of being focused around the other pieces that I felt were more important and I felt if I build something great, I’m going to be fine at the end of the day. So the private equity group got themselves into a place where they could, you know, pretty much have control over the entire board, where they got it pretty steep cliff around preferences, where they had to make their money back multifold first before founders like myself putting enough exit to a share of the exit. You know, those type of stories, I just got myself talked into without doing the due diligence and having the right setup of advisors around myself.

Drew: Yeah, absolutely. What sort of advice would you recommend to somebody else that was in that circumstance? Because I feel like a lot of people know they need to do those things but they don’t really know who to turn to or where to find somebody like that to kind of ask for advice.

Andreas: The hard one on the outside, especially if you are, like I’d mentioned, an organically growth, cash flow growth business. I mean, you grow up in a culture and with an orientation of I’m gonna try to save money wherever I can. And the one area where I saved the money that I would advise not to save money on is on the legal advice. That’s where it starts by getting yourself with a counsel that has had the experience of doing these type of deals. It doesn’t have to be a big law firm, but at least a practitioner, an independent even, that has done deals like that in the past who can advise you, who have sat across the table with the big guys and is not afraid of asking certain questions, and also knows the dynamics of a deal.

Because a legal advisor can show up, you know, by the book and be very regimented about the book and the terms or at least following your advice. But if they don’t understand the dynamic of a deal structure in the negotiation, they can kill the deal. So I did not pay the money. I did not get myself a legal counsel with that experience, which is the starting point I would give every advice to an entrepreneur that you really get yourself around to find the right person there.

Secondarily, again, if you are an independently growing company and you do not have a board and you have partners like the advertising agency I was talking about, like my business partner, we all didn’t have the experience ourselves. So can you find advisors being a friend, being people that you just reach out to? I mean, I know an individual here in town who runs a very successful business. She does a phenomenal job by literally asking friends and say, “I want to know somebody who has bigger, better business experience than I do. Can you please introduce me to that person?”

Like I could not do these type of jobs. Maybe I was shy, I don’t know. Maybe I felt like that I knew everything. I didn’t know what it was. But I just didn’t have this pool of advisors around me that I could go to and say, “Listen, here’s what I’m planning and do. What would you advise me to look out for you?” When I had the deal terms, send it to them, get their perspective. I didn’t have that. I was doing everything in isolation. And that is probably, in retrospect now, the biggest mistake that I’ve made that I went through this and crossed the finish line almost all by myself.

Drew: Yeah, absolutely. I think that’s probably one of the most common things we hear, as far as advice entrepreneurs get an advisory board or at least a peer group around you to bounce these types of decisions off. So out of the $6 million, how much did you have for growth, how much did you take off the table, and kind of what were your next steps from there?

Andreas: So didn’t take anything off the table. So all of that was for growth through an acquisition. So there was a whole build-out that we did on the, call it, sales and marketing side. And then the other component was all about, okay, how do we find acquisitions of, call it, smaller/same sized groups of agencies, right? And agencies there, specifically, were either a specialty capability that we didn’t have and we felt we were weakened or the other was just a geographical expansion/client expansion mode. So we invested about $1.5 million into sales and marketing over the course of multi-years and then the remainder, which was $4.5 million, we used in terms of deal flow and deal structure. So we ended up doing acquisition of five entities. I mean, everything from the web development shop to an SEO shop to an organic link-building shop in Philippines.

It was quite varied and part of the process was, also which I think is a big lesson or a thought process people have to go through, that my job function shifted quite a bit as well, right? So I came from a place of being an operator, company leader. You know, I rather focus on the CEO jobs but then once the rollout strategy is starting occurring, I found myself very heavily on the road and, you know, started to get tired of companies that felt that they might be a right fit, which actually in the process of acquisition, we did hire an M&A firm to do the legwork around it, right? So, as I mentioned earlier, I had private equity funds kicking the tires on me. We pretty much hired a firm to do the other, sit suddenly on the other side of the table. And we started doing mass outreach to companies with particular categories of criteria. And then they narrowed it down for me and I was the one who then put myself on the road, started meeting with, you know, over 40-some companies in various different parts of the country and it ended up actually in the world as well.

Drew: And so in terms of deal flow, were most of the deals that were presented that you ended up buying from the M&A firm or did you kind of have things that you brought in and identified on your own?

Andreas: Yeah, I did on my own as well. I’d probably say…that’s actually a really good question. I never even thought about this. I would say that all the deals that we did, only one came from that M&A firm.

Drew: Okay. So what were the terms with them?

Andreas: With the M&A firm?

Drew: Yeah.

Andreas: It was a typical give me four months auto retainer that you just have to pay and then a percentage of the acquisition cost so that when you swallow somebody or when you buy somebody.

Drew: So before you even brought them in, you kind of found the other four of the five just because you knew the industry?

Andreas: Yeah. The sequence is like throughout the course of five, six years, right? So it’s not like that it all happened all at once. So I think the first one was given to us, actually, got given to us. Once we had private equity, we had to form a board. So that was one of the requirements. And like I mentioned, you know, it was not in our preferences to board. One of the board members, however, was a very plugged-in industry veteran who brought to us the first deal. And that was a deal up in San Francisco. And so that was without anybody’s help.

And then the others came along in terms of having been around the industry, having built the brand, having done some PR as well, right? Because when you do an acquisition, you obviously want to blow it out from a marketing side as well. That you’re suddenly a bigger guy than you were before and obviously other companies take note of that and started reaching out to you as well. So that’s where the other CEOs came in, which is the one that which came out of the M&A firm deal.

Drew: In terms of kind of instruments you were using to finance these deals, were leveraging up on debt or, you know, mezzanine, or you were just using kind of profit or how did you finance all that?

Andreas: No, that’s all where the money can come, right? So the money that we used that came in from the prior regulation finance, all came in for that purpose. So there was no line…I mean, we had our typical line of credits for receivables and things like that. Not for the purpose of, you know, doing acquisitions. And I did not…

Drew: Go ahead.

Andreas: I’m not a fan of leveraging. I mean, that’s not, I guess, my orientation for leverage purposes. So that’s why I just stayed away from that. I mean it can make the whole deal much riskier to begin with. And I felt, you know, as soon as I was able to raise the money, it was no reason to do that.

Drew: Right. So you wanted to do some M&A but you wanted to wear your seatbelt?

Andreas: Well, I gave up my seatbelt but you’re right. Yeah.

Drew: With the deal.

Andreas: It was the seatbelt I was wearing from that standpoint, but I did give up the seat.

Drew: Yeah. Okay. Fair enough. And then we talked a little bit, you talked about geographic or specialty based. Were there any other type of targets or how you targeted companies for the roll-up?

Andreas: No, not really. I think those were the ones. I think it was both a geographical, which in this business like in digital marketing business back in those days, it was much heavier in terms of locale, right? So it was more service providers were used more based on proximity to a company to people wanting…you know, the video conferencing tool that they exist today did not exist back then. So people wanted to touch and see somebody. So, for us, locale expansion automatically meant client expansion as well. So that’s one component. And the other one was the service component that we just felt would accelerate with existing clients, our revenue base.

Drew: Yep. And I’m guilty of this from my past, but I know sometimes small, self-funded companies tend to greatly overvalue themselves and have this skewed view. You know, how did you deal with that? Because I’m assuming some of the companies you were buying were more on the smaller side and maybe owner funded and kind of, you know, that environment.

Andreas: Yeah, that’s a hard one. I mean, obviously, I had to learn as I went through this. At first, I didn’t understand that concept and that spend. Again, it goes back to when you do a rollout process, the key component is how do I spend my time as efficient as I can? Because otherwise…

Drew: Plus you’re German, Andreas.

Andreas: Yeah, and that’s on top of that but that’s not at all. You’re right. But, you know, you really have to be efficient and that means you have to get yourself in a place where you truly know what you’re walking into and make a decision if it makes sense for you to spend more time into it. And I didn’t do that at first. So I remember a situation. So it was a cool company. I think it was in Baltimore somewhere, a 12-people shop. They did something really cool. They actually built the technology around search engine optimization…not search engine optimization, paid search advertising, like that. But I walked into their office and the climate was just really startup-oriented. I spent too much time on these guys. I got infatuated by what they had, what they were doing. They didn’t have a sales process.

I knew exactly, that type of tool I can tell all day long. But technical guys, backgrounds were engineering oriented. It ended up later on that the mother of the founder had all the decisions and I met her and she was just the woman who thought she can give her son a big payout. She had no reality check with the revenue base that they had, etc., etc. So I spent months talking to these guys, talking about integration, talking about what type of role he would have in our company without pressing to the point of, “Okay, so how much is it going to cost?” Right, again, this is early on and I learned my lessons around that. And when we got to the point, eventually, it was just unbelievably what the guy wanted. I mean, the guy had probably, if I remember, $400,000 worth of revenue for the year, paid himself a salary of $30,000 or what it was, no profit on the bottom line and he asked for $5 million.

And, you know, you fall off your chair and you try to say, “Are you real? Do you understand what you’re doing? Do you understand you have no concept around how you got to the valuation?” So I try to work on that. And at the end of the day, emotionally, and in this case, also from a sophistication standpoint, there was just no base to negotiate around and that’s just the worst negotiation you can have. So I learned over the course, especially in first-time entrepreneur environments, small business settings that the key questions you have to ask around, “Okay, what’s your expectation around valuation?” as quickly as you can.

Secondarily, “What’s the expectation around the role thereafter?” Because typically, it’s one or two founders that are used to calling the shots. And if you are doing what I did, building a growing, rolling up organization, they very likely are not going to be calling the shots going forward. So are they comfortable in that environment? Are they truly willing to put that secondary and put themselves into an HR environment that they are just part of there? It sounds horrible but part of the game. And if that’s not truly put on the table upfront, then either you have a hard time and a waste of time effort when it comes to your acquisition approach. And if that’s not even the case and you get the deal done, even worse, it’s gonna fall apart post-acquisition, which is even worse, in my opinion.

Drew: Absolutely. And I remember, Brandon, you went through that early this year, I think you were trying to buy a company and there was like a son-in-law or some sort of role and all sorts of like hidden landmines to navigate to try to get a deal done that were not…you had to kind of uncover in the process.

Brandon: Yeah. I did the exact same thing. It was going to be an earn-out or a loan from the seller, and it all fell apart. And I think exactly what Andreas is saying, I could have…if now that I’m smarter and figured that out, I could have sorted out our first 20 minutes in the conversation, but I probably let that go on 3 months and probably spent 10 or 20 grand in time and lawyers. Like we were all the way up to where she was supposed to sign the LOI and we were just so off about a couple of tiny, tiny basic things. And I was like, “Oh, my gosh. Like this could have been addressed in an email before we even met in person or talked on the phone.” I think you just get so excited sometimes when you’re doing an acquisition and…

Andreas: Yeah. That’s the problem.

Brandon: …you’re so nerdy about the details.

Drew: Well, I think you get passionate about the vision, right? You just see how that company fits in so easy and you just want them to see it and you hope they will.

Andreas: Well, that’s the problem with entrepreneur. I mean the good and the bad thing about entrepreneur, right. We don’t look at the many times that the little hole on the path. We actually look at the finish line already, or we literally live the finish line already. And I think you’re absolutely right.

Drew: What was the largest company that you acquired and kind of maybe share any experiences, challenges, or highlights of that acquisition?

Andreas: Yeah, it ended up being the first one actually. It was a little bit over a couple mil of a deal, San Francisco. It’s an organization that was a superstar at one point before I came along, heavily funded also from the private equity standpoint, very well-respected, well-known brand in the industry. And they kind of like were on the downswing. Couldn’t figure out how to grow or actually turn themselves into a diminishing company. So I was able to catch them on the way down. In that environment, it was very interesting because they were at the point, I think, that we snapped it up in the 30s from an employee standpoint or staff size basis.

Office, obviously, in San Francisco, but it came along with all of those big organizational, I guess, settings or parameters that you can think of. San Francisco to begin with, like people live a little bit more lavishly than where we used to get down in San Francisco. Nothing wrong with that, if anybody’s from San Francisco listening. But it’s just the office space costs quite higher than what we’re used to down here. You know, the administrative or the operational side of the business was heavily stacked with, I remember, four people on the accounting department all the way to a high-paying CFO full time. And then the story just went on.

And so the interesting part around the deal is I inherited that type of structure on top of that type of culture as well. So here we were still, even after we got private equity, we were still this…and I don’t want to make this about San Diego versus San Francisco but we were kind of like this scrappy, roll up your sleeves type of culture versus this was a heavy private equity-funded, lavishly-oriented culture. So I had to figure out how to get that integrated, first of all. At the same time, I also had to do some cleanup on the financial structure, clients structure as well. So there was a lot of cleanup work we had to do.

But the biggest challenge really at the end of the day, which is where, as I say, if you want to summarize after two years after the acquisition, either it’s a natural because I’ve heard these stories and I’ve seen the stories multiple times or it’s simply a failure. We could not integrate that culture because the two years afterwards, if you do a summary line underwork, I think there was only one employee left from that group that we had acquired. So, like I said, it is a very natural and I think I would advise everybody that is acquiring companies, just go in with a belief that a large percentage of the people will leave you at one point in time, call it the next 12 to 24 months. And your objective needs to be how do I own, in this case, clients, processes, what’s unique about it, what can you adopt into it? Because those people that may help you be that, they might be gone.

So that’s something that I faced. It was discouraging for me because I like to be coming from a leadership place that is very heavy around culture, taking care of people. I believe that brings out the best in individuals and having seen kind of like having standing in front of my company-wide message talking about, “Oh, here’s another group of individuals who left the firm,” was really heartbreaking for me to begin with. I mean, it made me harder and tougher at the end of the day, but it’s just something that I had to deal with. And I think that my analysis of that is just we had a cultural clash based on simply the roots where this company came from.

Drew: Yeah, I know when I was involved in kind of the buying of the 10 companies that we consolidated, when people left, it felt like a personal attack on their trust in me and the vision that I was communicating, which maybe I shouldn’t have, but I probably took it a little more personal than I should have.

Andreas: Yeah. And what you try to do, you try to integrate, right, the firms as well. So, it’s not like, “Oh, here’s the San Francisco part of it and here’s the San Diego part of the business,” in this example. Like you’re trying to create a message, it’s one company, right? So with that, you also have to communicate company-wide the bad news versus just keeping it in the San Francisco office as a news item, right? And that was the hard part for me.

Drew: So you bought five companies. How big did you get at that point and kind of where did you see things going next?

Andreas: So at the end of the story, we were in the mid-30s as a company. And I was still that guy that started out with this big measurement bar that kept moving, right? I mean, if you ask me in 2000, could I build a $30-plus million company, I would of I told you, you know, this is fantastic and I’m done, right? Because that’s kind of like how I thought back then. But when you’re in the race, which may be also a learning for entrepreneurs that the bar just keeps moving because you feel it, you smell it, you get in a groove, you get excited, right, all of those and the bar just keeps moving.

So I felt that the mid-30s that I can go to a hundred. And so that’s what I was shooting for. That’s what I want to keep going right. I mean, I started turning up the volume quite a bit around international expansion, you know, obviously with my heritage around Europe. I started looking at deals in the U.K., in Germany. I even went all the way out to the Middle East to start looking there for deals because I did feel that was the next wave, which is kind of like the secondary markets that can be penetrated with “American super services.” So that’s what the path that I was on and then I don’t know if you want me to talk about that already.

Drew: Sure, yeah. What happened next?

Andreas: Yeah, so the whole then part was like the wind got taken out of my wings based on, as I’d mentioned, the destruction of decision-making dynamic that had changed when I got private equity because the private equity group…and for listeners, when you get the venture capital, private equity groups, they all live on a certain timeline. The fund has to provide returns to the investors over a limited period of time. And so there’s something that is a term that becomes very prevalent then called vintage fund, which is these funds that are expired. And investors pretty much just want to grab any type of money that they have because they’re done with investing in that fund.

So that’s just the scenario that we found ourselves in. That private equity group started pushing into a place where they said, you know, “It’s time to count our checks, or dollars,” whatever you want to call it, and I’m able just to return another amount of money to my investors. The interesting dynamic in a place where we found ourselves and many funds found themselves as well, if a private equity group or venture capitalist already has generated return, positive return to the investors, even if it’s a loss for them, or even if it’s an amount of multiplier from the investment that’s lower than what they typically go for, it’s still icing on the cake, right. And so their bar of getting out is not as aggressive as if they were still heavy in the game with the fund. Does that make sense?

Drew: Yeah.

Andreas: So that’s kind of like the dynamic we found ourselves without any decision-making power, despite the fact that I had the title of CEO. We were pushed into a place where we said, “Okay, let’s put ourselves up for sale.” And the decision, I was obviously against it, voted against it, but nothing I could do and we got ourselves out. A private equity firm actually started gathering the candidates themselves without my participation, but I had to obviously participate when it came to due diligence and others. And that was it. So in 2012, found a company that acquired that was backed by a Japanese private equity firm and they were in their own roll-up strategy that were actually smaller than we were but they used as a vehicle with the financial backing that they had in order to accelerate their roll-up. And there was the day where I pretty much completely handed over the control of what I had built in our sweat, blood, and whatever you want to call it over 12 years.

Drew: Absolutely. Was there a big payday at that point or what did that kind of look like for you when it closed with the Japanese private equity firm?

Andreas: I mean, big payday is always subjective, right? So everybody…I mean, depending what your goals are. It was meaningful…just call it that, it was meaningful enough for me to be able to live my future in a way that I can focus on doing the things that I feel are right. Let’s call it that. And there was payout and there was earn-out in that component. Earn-out-wise, I did okay. I didn’t get 100% of the earn-out and it got really, really messy because, I mean, the real ugly side of that story was that within a month of having handed over and leave, we were supposed to be on for a 12-month period as an “employee” or staff member. I got a phone call that pretty much told me at 8:00 in the morning and I needed to pack my stuff and leave and I’m not allowed to talk to anybody anymore. So it got a little bit messy on that end. And I guess that’s a learning that you can share with your audience as well that even if you think you got a rock solid, I don’t know what you wanna call, transition period, don’t count on it. Just prepare yourself, try to take as much as you can up front. The organization never looks like it did when you had control over it.

So if you’re in a place of shifting heavily to upfront versus earn-out, highly advise it. Don’t count on “salary” if that’s part of the equation because something might happen just the way it happened to me where you, out of nowhere, suddenly get the call that you have to play quits and then, you know, the next, I don’t even know, four or five months or so were just heavy legal, you know, from an employee standpoint, conversation with that group in order just to get a portion out of what was promised to me on that end. And, you know, that’s the ugly side of the picture. So I hope everybody just takes that and say, “All right, this is something that I have to look out for,” and then don’t let it happen the way it happened to me. But the good side is I am happy. You know, it was meaningful enough for me and I’m able to do the things that I love to do.

Drew: I know Brandon is selling a company, one of his companies right now, and I think he said, “Look, cash upfront is all I’m really gonna look at.” So what’s the most cash upfront? You know, it’d be interesting to kind of think like what is the dollar upfront versus, you know, is it worth $20 earn-out or like what’s the ratio between the two?

Andreas: Are you asking me?

Brandon: Even worse than that…Oh, go ahead.

Andreas: No, go ahead, Brandon. Sorry.

Brandon: Or even worse than that, the brokers of the deal take a half commission on what the potential earn-out could be. So I could actually lose money by taking a bigger earn-out.

Andreas: Yeah, that’s a great point. I mean, they take it on the total amount. So then they’re not gonna wait around two years, that’s the earn-out period, to get a check every quarter or something like that. They want it all. Totally. So I agree with you,

Brandon. I agree with you. That’s my mentality too. If the upfront money I can bring home under my bed is meaningful or right in terms of valuation, everything else is just icing on the cake. And that’s how I do deals nowadays myself.

Brandon: Absolutely. I think it removes a lot of tire kickers from day one as well. I kind of make that one of the first things I’m saying and it kind of gets rid of the people that are gonna come up and say, “Oh, you know, I’ll give you know 90% earn-out.” It kind of weeds all those people out right away.

Andreas: Right. So, I mean, on the opposite side, me having been on the buyer side, I did use that technique to lower my risk profile. It’s interesting to try to push earn-out when you buy but you don’t push it when you sell.

Drew: Absolutely. So you’re running this company for 12 years. It’s your baby. You are probably working 100 hours a week. And I’m interested in how you kind of felt when the money hit your account and you sold to the equity firm. And then kind of how those emotions, you know, change when you got that phone call it at 8:00 a.m. Like could you explain the kind of what you were going through and how you dealt with it emotionally kind both of those times? Because that’s kind of high highs and low lows.

Andreas: Yeah, totally. And then I’m a little bit weird from a standpoint of celebrating. I’ve known in this about myself over the years and people have told me many times. I’m not the guy who likes to celebrate. And that might actually come back to my athletic life because when you won a game, you pretty much came back into the locker room and your coach told you, “Get ready for the next game.” I’ve never done a really good job in celebrating, which was the case here as well. I mean, if you asked me, “Did I did I charter a private jet and flew to Vegas and had a weekend or something?” No, I didn’t.

And almost like just went ahead and went back to work Monday morning. But one thing that did change for me though was that I suddenly started acting differently in terms of decision making. Because, you guys know this as well, if you are an entrepreneur that has put everything into it, you also have a lot of behavior that’s based on fear and anxiety of losing and, you know, kind of like everything being taken away from. And I felt on the day when the money hit, that that was taken away from me. That I could actually start working from a place of strength and really, you know, knowledge versus having this other layer of fear that constantly, you know, it plays with my mind to an extent. So that’s what happened there.

When I got let go, that was probably for me the most extreme emotional experience I’ve had in my life because also the way it happened was so abrupt. It was done in a way that, you know, in retrospect, I did not get any dignity in front of the people that I put words in front of, you know, for years because my entire team did not know, my cell phone was turned off, my email address was turned off. I was in a place where for 12 years, I used my work email as my life email. So I didn’t even know what my Gmail password was. I couldn’t even get in.

So I literally felt on the day I will never forget that I find myself on the beach, luckily in San Diego, we can sit at the beach at 2:00 in the afternoon. And I thought, “What an F-ing loser am I sitting here at 2:00 in the afternoon? I didn’t have any meetings. I didn’t have any calls. I can’t check any email. What am I gonna do?” So I fell into this big, big hole of feeling not worth anything anymore suddenly. And I struggled with that a lot.

And, you know, this is a learning I would have for anybody that’s selling a business that you need to emotionally prepare yourself for the day when you are not anymore, you know, on your LinkedIn profile that title, when your email address changes, when you’re not being asked anymore to speak in certain speaking engagements [inaudible 01:01:30] because it’s a big hit for you if you’re not prepared for that. So I always advise people…I mean, I had a friend who sold a business within the $50 million range. And I told him the best advice I can give you is find a counselor before you sell the business and start preparing yourself for that. And he did and he came back to me and he said that was probably the most brilliant advice. Yes, it was me who gave him advice.

Drew: You said the same thing to me, by the way. I went to counseling and did…Oh, my gosh.

Andreas: I did? Oh, okay, so I did it with you as well. I’ve been sharing that message because he came back to me and gave me that positive, you know, feedback. And I was so happy to see that because I don’t want anybody to go through and mostly what I went through because it really drained me and made me ask who I am and what my purpose is going forward. Even if you have money, as an entrepreneur you wanna know what’s next. It’s just who we are.

Drew: You know, I think that was the biggest shock for me was this sense of identity change, where it’s like, you had this whole identity that you built around that company and who you were as the CEO, as the founder, and all of these things that you had kind of like constructed around your sense of self and then all of them are removed in an instant. It is shocking.

Andreas: Yeah, yeah. So l would like to…

Drew: Go ahead.

Andreas: No, I just said that unless you’re just a money-driven guy that celebrates when the check comes in and you don’t care about anything else, what you just said,

Drew, you know, that’s gonna be actually your biggest question you have to answer yourself before, you know, cross the finish line.

Drew: Yes. And it’s amazing how few people are really prepared for that. I mean, anything else that you would say, I mean, you know, you were going to counseling. I mean, I think you talked about, you know, depression. I mean I know I went through a roller coaster of emotions and, you know, it worked, just to kind of process through that.

Andreas: Yeah. No, I mean, after a period of time like I did take some time off. And so call it month eight or so after, you know, having exited you start questioning also your, I don’t know, management skills, any type of skill that came so natural to you, analytical thinking processes. And, you know, being an athlete, I kind of like found myself doing individual sports. So not in a group. And I didn’t have much group dynamics anymore. And I think that’s another piece on the intangible side of an advice is, you know, find yourself places where you can be in group dynamics because it’s just really important to stay social.

Be able to mark in your calendar events that you can go to where you can get dressed up and do these types of things. And just so you feel like you’re still in the game and you still got it. Because when I started the next company, I really literally felt for the first three months or so, I had to remember all these things that are used to do, you know, how I was running meetings, how I was organizing myself, how, you know, I was able to touch people from a leadership side so they become effective. Like those things, I felt I had a bit of a ramp up again.

Drew: Anything else that you kind of learned about yourself even in that eight-month period of being off where a lot of the kind of identity around work was stripped away? You know, were there things that you discovered about yourself for the first time or that kind of came more to light?

Andreas: Yeah, I did. And, you know, I’m kind of like always this, how can I cramp so much stuff into my day? So, you know, that’s for me an element of feeling like I’ve done a good job today. The one thing in terms of my counselor…and I might have shared this with you too, Drew. The best advice she gave me was, “It’s time and great to water plants.” And obviously, I didn’t understand at first what she meant with that but having the ability to really slow down, if you’re this high-charging, always going individual and finding these moments where you can really water the plants has helped me now even not having been like full of juice to really find these pockets [SP] because that revitalization is so incredibly important and I didn’t have that. And with a revitalization, you know, you guys know this, we find a space to think about the purpose of what you do on a day-to-day basis, which then revitalizes you actually when you do the work. And I think that was one of the big learnings that I still practice today that I feel makes me also much more effective than I was back in those days.

Drew: Yeah, I’m about six months off of work from kind of stepping down. And, man, I feel like a lot of huge breakthroughs have come in the last six months that I now have the time and space really to deal with. So it’s been a blessing that I didn’t foresee.

Andreas: Yeah, good for you.

Drew: Well, good. Go ahead, Brandon.

Brandon: Yeah. You know, you cooled down a little bit and kind of reflected. What was your next steps and kind of what are you working on these days?

Andreas: Well, next up was that people started bugging me that…you know, over the years you always try to see what else can I do and in parallel to what you’re already doing. So I’ve always had these conversations with folks and some of them started bugging me, first jokingly, saying, “Hey, you don’t do anything anywhere, why don’t we do what we said we were gonna do later on becoming more concrete.” So one of those was a gentleman that became a friend who had been in the Middle East, Dubai specifically, where we kind of like always had the thesis that the Middle East is two years behind based on the internet specifically and techniques and tactics around the internet around what’s happening in the U.S.

So he convinced me or he actually called me up one day and he said, “Listen, we always talked about doing something. How about I secured the licenses of all the major TV and movie production companies in the Middle East, all Arabic, and can we do something with that?” So I started looking into that. And the outcome of that was that I showed up at my wife’s doorstep and asked to move for a period of time to the Middle East, to Dubai. And we started a video-on-demand platform. Well, what people started calling The Ruler of the Middle East, which ended up to be the fastest growing in that region. So I did that for a little bit over a year-and-a-half. Had a successful exit out of it to one of the licensing companies.

Obviously, it was a great experience in terms of, you know, running a fast-growing business, you know, having a nice earn-out…exit, I’m sorry. And then also what was the most fascinating, what region and the leadership of our region because I was able to get a team together out there. The team members all come from Palestine, Egypt, Turkey, Lebanon, India, Philippines. It was like the United Nations to kind of figure out how to manage. So that was fascinating. I did that for a little bit over a year-and-a-half.

And then, you know, I already started looking back into what I can do when I come back to San Diego. Started to work the end building up a business, which is one of the businesses that I have right now called Katana, which is a digital marketing paid media service provider, technology provider. I did that with several of my former leaders of my first business that I sold, all the people that did really well for me, for the business. I had all the trust in the world in that. And so it was kind of like very wonderful to bring them back together and start something.

It also gives them the chance to feel like going from an employee status into an ownership status. And it’s just beautiful to see the company has been around now a little bit over three years. And just seeing how these individuals are coming along is a wonderful bliss for me. And then in parallel what I’ve done, partnered up with two folks and we raised money. We currently have raised over $12.5 million and have what’s called a venture incubation fund where we start companies specifically around artificial intelligence. That’s where I spend my…like between those two sides of the business, that’s where I pretty much I spend all my juice nowadays.

Brandon: That’s great. When you were talking about the Middle East, it reminded of a book I read, the Ted Turner biography called “Call Me Ted.” Have you ever read that?

Andreas: I have not.

Brandon: You should read that. I think you’d like it. It’s a great, great book.

Drew: It reminded me of the Chris Farley interview when he’s like, “Have you seen that movie? That movie is great.”

Andreas: No. You guys need to send those to me. I want to check those out.

Drew: All right.

Brandon: Well, great, Andreas. I think that definitely helps. A lot of really good points there. And how can people stay in touch with you if they kind of wanna learn more about Analytics Ventures and what you’re doing and kind of follow your path on that?

Andreas: Sure. Absolutely. I’ll give you my email address. I’m happy to receive and answer any questions. It’s andreas@analytics-ventures.com.

Drew: Awesome. I appreciate you taking some time. Yeah, a fascinating story, a lot to learn from, and we look forward to seeing what continues to come from the work that you’re doing.

Andreas: Thank you guys for having me. I really appreciate it and I wish you guys all the best of luck.